Metropolitan Portland has been grappling with issues of Smart Growth for years. Its Nature in Neighborhoods program recognizes that greenspace is an important amenity for residents:

Section 1. Intent

The purpose of this ordinance is to comply with Section 4 of Title 13 of Metro’s Urban Growth Management Functional Plan.

A. To protect and improve the following functions and values that contribute to fish and wildlife habitat in urban streamside areas:

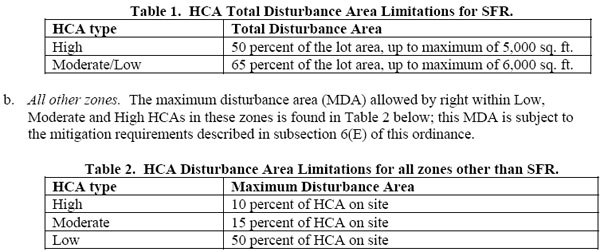

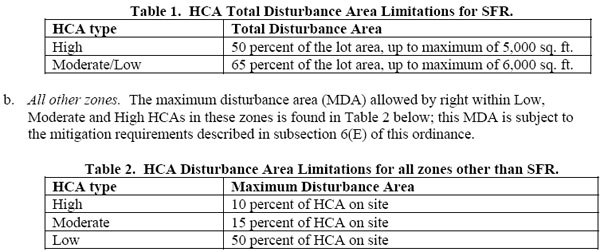

[HCA: Habitat Conservation Area; SFR: Single-Family Residential]…

…

…

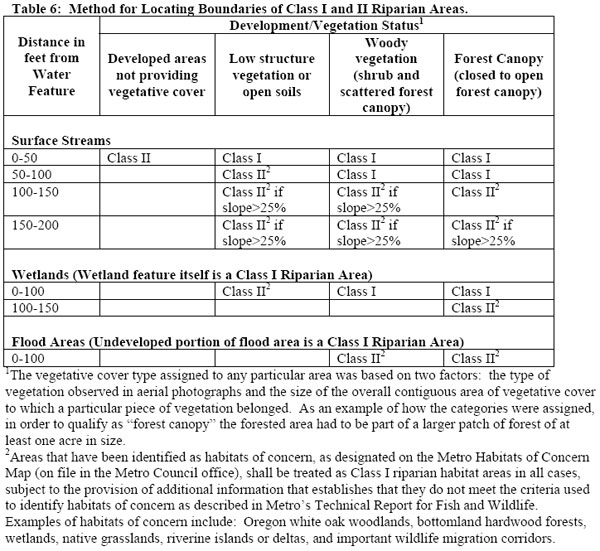

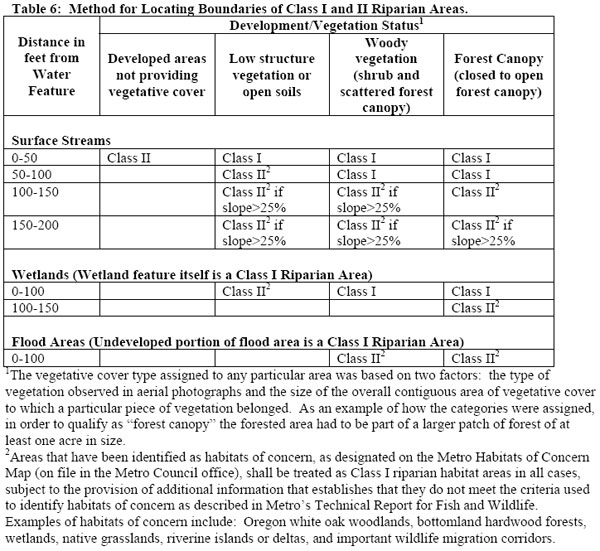

Forest canopy is considered to be “areas that are part of a contiguous grove of trees of one acre or larger in area with approximately 60% or greater crown closure, irrespective of whether the entire grove is within 200 feet of the relevant water feature.”

It appears to us that that the woodland/wetland area behind North Street, proposed for development by Kohl Construction, is exactly the kind of ecology that the Portland model ordinance is trying to preserve. Even if classified as having “High Urban development value”, the forested area within 100 feet of the wetland would appear to qualify as a Class I Riparian zone and a Moderate Habitat Conservation Area. This in turn, would appear to cap the allowable disturbance of this area to 15% of the site, unless it was dedicated to single-family homes.

It’s unfortunate that Northampton’s new Wetlands Ordinance encourages development as close as 10 feet to wetlands in our more built-up areas. There is much to be learned from the experience of the West, which has witnessed the effects of rapid growth in formerly green areas.

See also:

The Economic Value of Wetlands: Wetlands’ Role in Flood Protection in Western Washington

…Episodic flooding along rivers and streams in the lowlands of Western Washington has become a recurrent theme of recent years. Development practices that eliminate or compromise natural systems capable of controlling runoff appear to be exacerbating flooding problems in many areas. This highlights the importance of the remaining natural systems capable of attenuating flood flows, particularly wetlands, in the region’s defenses against increasingly destructive floods…

The analysis suggests that communities are likely to pay an increasingly high price for flood protection if they allow their remaining natural systems capable of attenuating flood flows to become further compromised in their ability to do so…

More than half of the wetlands that once existed in western Washington have been lost. Often the cause has been agricultural conversion, but today wetlands are increasingly at risk due to urban and suburban development. Western Washington is now one of the fastest growing regions of the country, and the remaining wetlands in rapidly developing areas are increasingly valuable for the flood protection they can provide. At the same time, the increasing pace and density of development is resulting in the natural wetlands systems that are capable of absorbing urban runoff becoming ever more fragmented, even as the need for flood protection grows ever more critical…

Studies have shown that flood peaks may be as much as 80 percent higher in watersheds without wetlands than in similar basins with large wetland areas (U.S. ACOE 1976)…

Northampton Redoubt: Urban Ecology, Planting Trees, and the Long-Term View

If we remove all of our in-town forested areas and wetlands they will likely be gone forever or at least a very long time. We would do well for posterity to err on the side of caution. For example the cost estimate to restore part of the downtown historic Mill River channel runs into the millions of dollars. Had the river’s diversion in the 1940s been handled differently, perhaps with a sharper eye towards the future, maybe today we wouldn’t be searching for dollars to make its restoration a reality.

Connecticut River Watershed Action Plan: Remove impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams

To reduce nonpoint source pollution from stormwater runoff, the Connecticut River Strategic Plan proposes the removal of impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams and the investigation of “functional replacements” (such as the use of permeable pavement) for impervious surfaces within 100 feet of streams, in developed areas (PVPC, 2001). In the urbanized areas, the removal or retrofitting of impervious areas and the implementation of Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMPs) could be beneficial in improving water quality. The interception and redirection of stormwater, that would otherwise enter storm drains and CSOs, would contribute to the reduction of peak flow during heavy storms. One example is to collect runoff from roofs for use in lawn irrigation.

…Areas with high percentages of impervious surfaces are most likely to be affected by increase stormwater runoff into rivers and streams. (p.46)

Intermittent Streams Merit a 100-Foot Buffer Zone in Hopkinton

Here is a bylaw from Hopkinton’s Wetlands Protection Regulations (PDF) requiring a 100-foot buffer zone around intermittent (and continuous) streams. We note that just such an intermittent stream, Millyard Brook, runs through the heart of the forest behind North Street that Kohl Construction intends to build on.

Berkeley Downtown Area Plan Advisory Committee (DAPAC): “Environmental Sustainability”

Adopted by Subcommittee on September 11, 2007

Urban Forest. Downtown Berkeley needs more trees. Trees have significant environmental, aesthetic, and economic benefits. Air quality authorities across the country are promoting planting programs for street trees and other trees in urban areas to reduce high temperatures absorbed by unshaded asphalt. Heat increases the ozone from automobile exhaust, which contributes to smog and respiratory ailments. Shaded streets are significantly cooler on summer days and help to reduce smog. Street trees will also play a major role in enhancing Downtown’s character and charm, and giving it a special sense of place…

Stormwater. Pollution from urban runoff (stormwater) is the greatest contributor to degraded water quality in the Bay Area. Increased urban runoff is a direct consequence of development and the associated loss of natural water retention and filtration through the installation of impervious surfaces. Berkeley does not meet the current, state-mandated water quality standards for urban runoff. Meanwhile, the state standards are themselves becoming even more stringent, suggesting that the City will be hard-pressed to comply with future regulations using its existing stormwater treatment

approaches.

At the same time, engineered stormwater treatment systems, which were installed 50-60 years ago, are now failing throughout the Bay Area (and California) as they reach the end of their projected “lifespans.” Berkeley’s stormwater system repair costs were recently estimated to be in the range of $100 million or more.

Green strategies for stormwater treatment are being implemented throughout the Pacific Northwest, and in other parts of California, as a more cost-effective, and multi-benefit solution to the challenges outlined above. Specifically, green approaches include: reducing impermeable surfaces, adding vegetation and soils that can absorb and filter stormwater, and restoring natural waterways and/or creating natural drainage swales to complement the engineered stormwater treatment systems now in existence…

Maintain mature trees wherever possible. Permit the elimination of mature trees only in instances of disease or overriding public benefits, and only after opportunities for public comment. Establish standards and guidelines for replacement trees for instances when tree removal is unavoidable.

Alewife Study Group: Impact of Development on Wetlands and Flooding

…As a direct result of development on the Alewife flood plain and its low elevation, there is periodic and significant flood damage in the surrounding communities. A 1981 study by the MDC found property damage in the Alewife area to be the highest of any portion of the Mystic River watershed of which it is a part.

UK Blog: Floods and Development, 7/23/07

…the LibDem Councillors, at a recent Cabinet meeting produced documents promoting an increase in “high density developments” in Teddington, Whitton and Twickenham. This is an issue I will come back to as a separate debate on planning, but given the flood risks in the area, should we really be concreting over our green spaces and further reducing drainage potential and increasing flash flood risk?

The Portland metropolitan region is set in an exceptional natural landscape. It is surrounded by hills and mountains and laced with rivers and streams. It is a region of national distinction for clean water, clean air, outdoor recreation, and an abundance of green; a place where nature is always nearby. This tremendous natural inheritance sustains residents’ health, fosters the region’s economy, provides healthy activities for all and is central to the region’s identity.Metro Portland provides a Nature in Neighborhoods model ordinance to help cities and counties implement habitat protection. This model provides a crucial bridge between laudable goals, such as the support for tree canopy in the Sustainable Northampton Plan, and the specific laws that can implement these goals:

The Metro Council launched Nature in Neighborhoods in 2005, concluding years of contentious deliberations about a state-mandated regulatory framework called “Goal 5” and ushering in an era of public/private innovation, investment and collaboration.

Metro plays a lead role in Nature in Neighborhoods but recognizes that the protection and restoration of fish and wildlife habitat and the integration of natural areas into the urban environment urban environment eclipse the reach of any one organization; they require the coordinated and strategic action of many.

Today, hundreds of organizations region-wide are working together to fulfill the vision of Nature in Neighborhoods. Projects range from neighbors volunteering on small restoration projects on the region’s creeks and rivers to multi-year professional habitat enhancement efforts and everything in-between, all captured in REIN.org, the region’s first comprehensive clearinghouse for information on conservation initiatives, to the $227.5 million Nature in Neighborhoods Natural Areas Bond Measure approved by voters in November 2006, the largest urban conservation acquisition initiative in the United States in decades.

The Metro Council continues to provide active leadership to Nature in Neighborhoods with a commitment to a legacy of regional parks, natural areas, wildlife habitat, clean air and clean water for this and future generations.

Section 1. Intent

The purpose of this ordinance is to comply with Section 4 of Title 13 of Metro’s Urban Growth Management Functional Plan.

A. To protect and improve the following functions and values that contribute to fish and wildlife habitat in urban streamside areas:

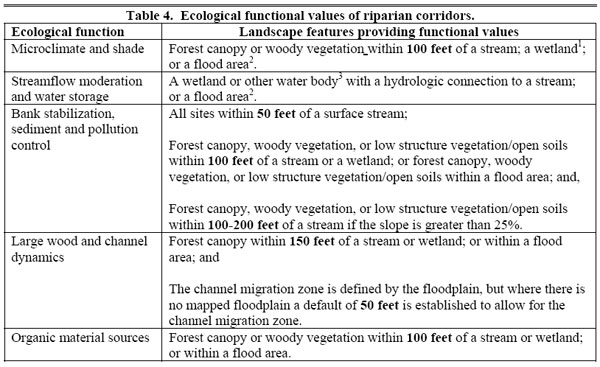

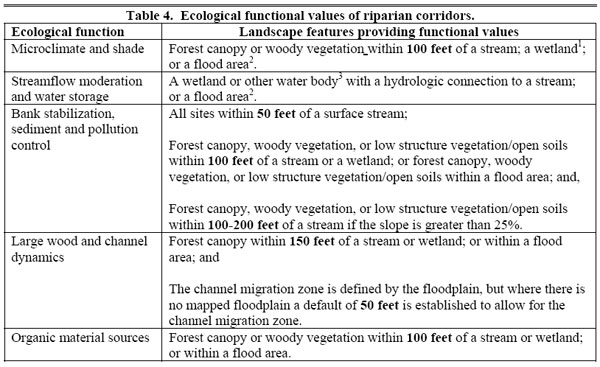

1. Microclimate and shade;B. To protect and improve the following functions and values that contribute to upland wildlife habitat in new urban growth boundary expansion areas:

2. Stream-flow moderation and water storage;

3. Bank stabilization, sediment and pollution control;

4. Large wood recruitment and retention and channel dynamics; and

5. Organic material sources.

1. Large habitat patches

2. Interior habitat

3. Connectivity and proximity to water; and

4. Connectivity and proximity to other upland habitat areas…

[HCA: Habitat Conservation Area; SFR: Single-Family Residential]…

…

…

Forest canopy is considered to be “areas that are part of a contiguous grove of trees of one acre or larger in area with approximately 60% or greater crown closure, irrespective of whether the entire grove is within 200 feet of the relevant water feature.”

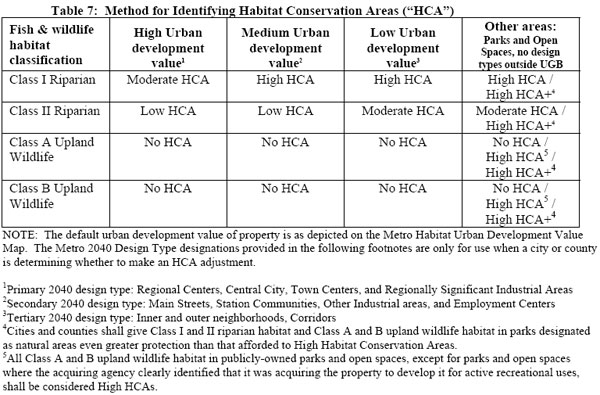

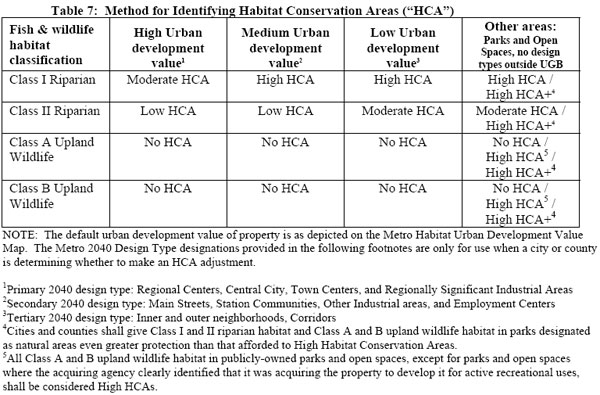

It appears to us that that the woodland/wetland area behind North Street, proposed for development by Kohl Construction, is exactly the kind of ecology that the Portland model ordinance is trying to preserve. Even if classified as having “High Urban development value”, the forested area within 100 feet of the wetland would appear to qualify as a Class I Riparian zone and a Moderate Habitat Conservation Area. This in turn, would appear to cap the allowable disturbance of this area to 15% of the site, unless it was dedicated to single-family homes.

It’s unfortunate that Northampton’s new Wetlands Ordinance encourages development as close as 10 feet to wetlands in our more built-up areas. There is much to be learned from the experience of the West, which has witnessed the effects of rapid growth in formerly green areas.

See also:

The Economic Value of Wetlands: Wetlands’ Role in Flood Protection in Western Washington

…Episodic flooding along rivers and streams in the lowlands of Western Washington has become a recurrent theme of recent years. Development practices that eliminate or compromise natural systems capable of controlling runoff appear to be exacerbating flooding problems in many areas. This highlights the importance of the remaining natural systems capable of attenuating flood flows, particularly wetlands, in the region’s defenses against increasingly destructive floods…

The analysis suggests that communities are likely to pay an increasingly high price for flood protection if they allow their remaining natural systems capable of attenuating flood flows to become further compromised in their ability to do so…

More than half of the wetlands that once existed in western Washington have been lost. Often the cause has been agricultural conversion, but today wetlands are increasingly at risk due to urban and suburban development. Western Washington is now one of the fastest growing regions of the country, and the remaining wetlands in rapidly developing areas are increasingly valuable for the flood protection they can provide. At the same time, the increasing pace and density of development is resulting in the natural wetlands systems that are capable of absorbing urban runoff becoming ever more fragmented, even as the need for flood protection grows ever more critical…

Studies have shown that flood peaks may be as much as 80 percent higher in watersheds without wetlands than in similar basins with large wetland areas (U.S. ACOE 1976)…

Northampton Redoubt: Urban Ecology, Planting Trees, and the Long-Term View

If we remove all of our in-town forested areas and wetlands they will likely be gone forever or at least a very long time. We would do well for posterity to err on the side of caution. For example the cost estimate to restore part of the downtown historic Mill River channel runs into the millions of dollars. Had the river’s diversion in the 1940s been handled differently, perhaps with a sharper eye towards the future, maybe today we wouldn’t be searching for dollars to make its restoration a reality.

Connecticut River Watershed Action Plan: Remove impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams

To reduce nonpoint source pollution from stormwater runoff, the Connecticut River Strategic Plan proposes the removal of impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams and the investigation of “functional replacements” (such as the use of permeable pavement) for impervious surfaces within 100 feet of streams, in developed areas (PVPC, 2001). In the urbanized areas, the removal or retrofitting of impervious areas and the implementation of Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMPs) could be beneficial in improving water quality. The interception and redirection of stormwater, that would otherwise enter storm drains and CSOs, would contribute to the reduction of peak flow during heavy storms. One example is to collect runoff from roofs for use in lawn irrigation.

…Areas with high percentages of impervious surfaces are most likely to be affected by increase stormwater runoff into rivers and streams. (p.46)

Intermittent Streams Merit a 100-Foot Buffer Zone in Hopkinton

Here is a bylaw from Hopkinton’s Wetlands Protection Regulations (PDF) requiring a 100-foot buffer zone around intermittent (and continuous) streams. We note that just such an intermittent stream, Millyard Brook, runs through the heart of the forest behind North Street that Kohl Construction intends to build on.

Berkeley Downtown Area Plan Advisory Committee (DAPAC): “Environmental Sustainability”

Adopted by Subcommittee on September 11, 2007

Urban Forest. Downtown Berkeley needs more trees. Trees have significant environmental, aesthetic, and economic benefits. Air quality authorities across the country are promoting planting programs for street trees and other trees in urban areas to reduce high temperatures absorbed by unshaded asphalt. Heat increases the ozone from automobile exhaust, which contributes to smog and respiratory ailments. Shaded streets are significantly cooler on summer days and help to reduce smog. Street trees will also play a major role in enhancing Downtown’s character and charm, and giving it a special sense of place…

Stormwater. Pollution from urban runoff (stormwater) is the greatest contributor to degraded water quality in the Bay Area. Increased urban runoff is a direct consequence of development and the associated loss of natural water retention and filtration through the installation of impervious surfaces. Berkeley does not meet the current, state-mandated water quality standards for urban runoff. Meanwhile, the state standards are themselves becoming even more stringent, suggesting that the City will be hard-pressed to comply with future regulations using its existing stormwater treatment

approaches.

At the same time, engineered stormwater treatment systems, which were installed 50-60 years ago, are now failing throughout the Bay Area (and California) as they reach the end of their projected “lifespans.” Berkeley’s stormwater system repair costs were recently estimated to be in the range of $100 million or more.

Green strategies for stormwater treatment are being implemented throughout the Pacific Northwest, and in other parts of California, as a more cost-effective, and multi-benefit solution to the challenges outlined above. Specifically, green approaches include: reducing impermeable surfaces, adding vegetation and soils that can absorb and filter stormwater, and restoring natural waterways and/or creating natural drainage swales to complement the engineered stormwater treatment systems now in existence…

Maintain mature trees wherever possible. Permit the elimination of mature trees only in instances of disease or overriding public benefits, and only after opportunities for public comment. Establish standards and guidelines for replacement trees for instances when tree removal is unavoidable.

Alewife Study Group: Impact of Development on Wetlands and Flooding

…As a direct result of development on the Alewife flood plain and its low elevation, there is periodic and significant flood damage in the surrounding communities. A 1981 study by the MDC found property damage in the Alewife area to be the highest of any portion of the Mystic River watershed of which it is a part.

UK Blog: Floods and Development, 7/23/07

…the LibDem Councillors, at a recent Cabinet meeting produced documents promoting an increase in “high density developments” in Teddington, Whitton and Twickenham. This is an issue I will come back to as a separate debate on planning, but given the flood risks in the area, should we really be concreting over our green spaces and further reducing drainage potential and increasing flash flood risk?