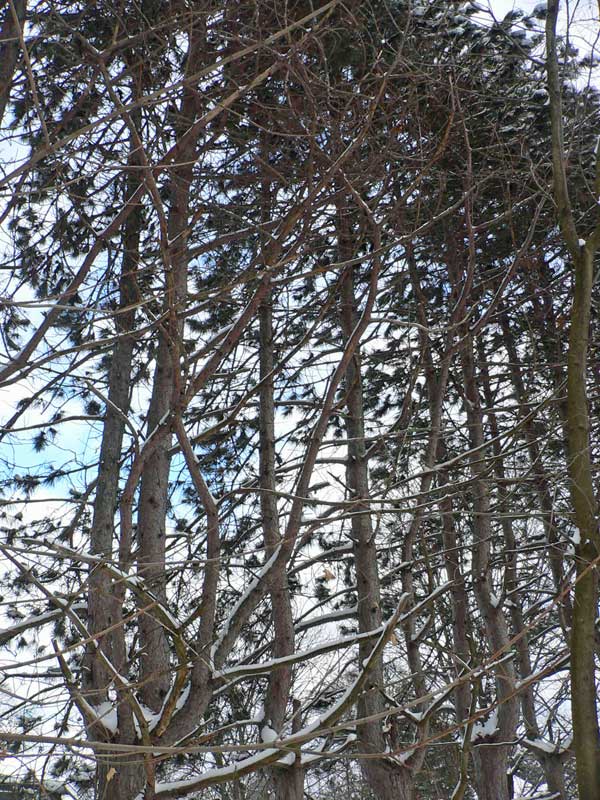

In Livable Streets, Donald Appleyard lists 10 reasons people like trees on their street (p.66). We’ve woven those reasons around some new pictures of the trees around North Street and the woods behind…

1. They provide shade.

2. They make the street more alive by their movement and richness.

3. They are soothing to the eyes.

4. They purify the air and increase the oxygen content.

5. They hide buildings.

6. They add a sense of privacy.

7. They provide contact with nature and give warmth as opposed to the hardness of cold concrete.

8. They cut down on noise.

9. They can make the streets look neat and provide residents with an opportunity to show they care for them.

10. They provide an identity if they are unique…

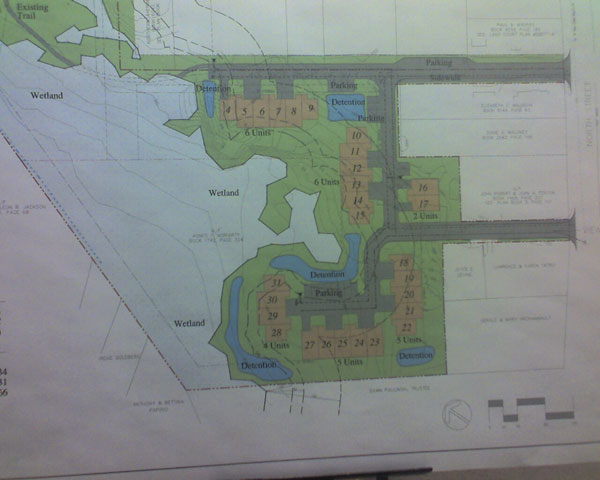

The environment above faces threats from two directions. First, Kohl Construction proposes to replace a good chunk of the North Street woods with around two dozen cookie-cutter condos…

plus their attendant roads, parking lots and detention pools…

Second, trees around homes in Northampton’s built-up areas (where perhaps half the population lives) may be threatened by proposals in the Sustainable Northampton Plan, which encourages city officials to “implement ideas for maximizing density on small lots” (p.14) and “consider amending zero lot line single family home to eliminate 30′ side yard setback” (p.67).

If you walk down North Street, imagine most trees between houses gone and replaced with a near-solid wall of housing. See the articles below, and decide if that’s growth that’s smart, or growth that smarts…

“Planning for Trees” by Henry Arnold, Planning Commissioners Journal, January/February 1992

A recent survey by the American Forestry Association of twenty American cities found that, on average, only one tree is planted for every four removed…

Our urban centers need to become more attractive to help counter the continuation of a sprawl pattern of development. If the appeal of low density, widely scattered development is derived from the need to be closer to nature, then making trees an integral part of the urban habitat will help make our town and city centers more desirable places to live and work. It is profoundly important to see this linkage between making cities and towns more “liveable” and stemming the continued spread of scattered development across the countryside.

“Green Enhances Growth” by Edward T. McMahon, Planning Commissioners Journal, Spring 1996

…today, tree protection ordinances are sprouting up all over the country. In California and Florida alone almost two hundred communities now have city tree ordinances…

In 1991, the [Urban Land Institute], in cooperation with the American Society of Landscape Architects, examined eleven real estate developments to assess whether money spent on site planning, landscaping, and preservation of mature trees justified the added cost of development…greenspace and landscaping translated into increased financial returns of 5 to 15 percent depending on the type of project. Landscaping also gave developers a competitive edge and increased the rate of project absorption…

[A National Association of Home Builders] report points out that “lots with trees sell for an average of 20 to 30 percent more than similarly sized lots without trees,” and that “mature trees that are saved during development add more value to a lot than post construction landscaping.”

…[A 1995 survey by American Lives shows] that “consumers are putting an increasingly high premium on interaction with the outdoor environment through the inclusion of wooded tracts, nature paths, and even wilderness areas in housing developments.” In fact, 77 percent of consumers put “natural open space” as the feature they desired most in a new home development.

[Appleyard’s ’10 reasons people like trees’ is quoted in a sidebar in McMahon’s article]

“Growing Greener: Conservation Subdivision Design” by Randall Arendt, Planning Commissioners Journal, Winter 1999

A national survey of homebuyers conducted in 1994 by American Lives revealed that of 39 features critical to their choice, homebuyers ranked “lots of natural open space” and plenty of “walking and biking paths” as the third and fourth highest rated factors affecting their decisions…

Although the groundwater impact of an individual development may not be terribly significant, the cumulative effect of hundreds of acres of native woodland and meadows being evenly graded and covered with streets, driveways, patios, rooftops, and lawns (which allow for a surprisingly high amount of runoff) can be very considerable.

“On the Value of Trees and Open Space” by Elizabeth Brabec, Planning Commissioners Journal, Summer 1993

Trees reduce air pollution by filtering dust out of the air, reduce noise and light pollution, reduce soil erosion and water run off, and aid in climate control. Research has shown that properly placed trees and landscape plantings can save 20 to 25 percent of energy use in the home for both cooling and heating…

Numerous studies have shown that people are willing to pay more for homes that are surrounded by trees and other landscaping. How much more? Depending on the area of the country, anywhere from 3 to 18 percent…

Municipal tree programs are often the first part of the municipal budget to be cut. Yet trees are the only part of the municipal infrastructure that actually increases in value every year. Trees not only increase in their individual value, but they also add to adjacent property values. This, in turn, leads to increased tax revenues for the municipality–and often to the revitalization of residential and commercial areas.

As with trees, parkland and open space can have a positive impact on the economy of a commun

ity by adding to the value of adjacent property. Depending on the region and study parameters, open space has been found to add 5 to 33 percent to the value of adjacent property…

“Green Infrastructure” by Edward T. McMahon, Planning Commissioners Journal, Winter 2000

Just as communities need to upgrade and expand their gray infrastructure (i.e. roads, sewers, utilities), so too, they need to upgrade and expand their “green” infrastructure–the network of open space, woodlands, wildlife habitat, parks and other natural areas, which sustain clean air, water, and natural resources and enrich their citizens’ quality of life…

The concept of green infrastructure represents a dramatic shift in the way local and state governments think about green space. In the past, many communities assumed that open space was land that had simply not been developed yet, because no one had filed a subdivision plan for it…

More homebuyers today favor housing developments that include green space, biking and pedestrian paths, and natural areas…

Strategies for revitalizing urban cores are increasingly emphasizing the value of natural areas within the city such as waterways, parks, and other green corridors…

Designated routes, such as rail-trails and greenways, provide access to and appreciation of the values of natural areas and other green spaces, present diverse resource-based outdoor recreational opportunities, and enhance the understanding of historical sites and cultural diversity…

…green space is not a frill–it is a basic community building block.

See also:

Northampton: Dr. Rutherford Platt to Speak on The Humane Metropolis, March 9

Sunday, March 9, at 7 p.m.

Edwards Church

299 Main Street at corner of Main and State

Northampton, MA

This program is free and open to the public.

The Ecological Cities Project: Greenspace in “The Humane Metropolis”

A metropolis (i.e., metro region or citistate) is considered green if it fosters humans’ connections to the natural world — an idea Anne Whiston Spirn promoted in her seminal 1984 book The Granite Garden. Spirn rejected the idea — easily absorbed if one watches too many “concrete jungle” films, or even televised nature documentaries — that the natural world begins beyond the urban fringe. “Nature in the city,” she wrote, “must be cultivated, like a garden, rather than ignored or subdued.”

Rutherford Platt, “Regreening the Metropolis: Pathways to More Ecological Cities”

…cities and metropolitan areas, now too large to conveniently escape, must themselves be viewed as incorporating both built and unbuilt environments… And into the bargain, the urban environment will prove to be more habitable, more sustainable, more “ecological”…

Irony of Infill: You Have to Drive to Enjoy Nature

Vancouver Sun: “Call it EcoDensity or EcoCity –either way it’s a hard sell”

Despite Yaletown, almost 70 per cent of the city is single-family housing. Vancouver, essentially, remains an urban suburb. And there is a reason for this.

People love it.

They love the city’s garden-like nature. They love the stability and social cohesion of a single-family neighbourhood. They like having neighbours they know…

…A group called Neighbourhoods for a Sustainable Vancouver — which itself has said it is in favour of densification, but only if properly planned — has signed up almost 30 community organizations in every neighbourhood in the city to oppose “the city’s plan to densify neighbourhoods without plans to ensure adequate safeguards or amenities.”

Suburban ‘Raise the Drawbridge’ Sentiment Motivates Some Smart Growth Policies

Steven Greenhut, a columnist for the Orange County Register, says that Smart Growth policies that ignore people’s living preferences will fail and make things worse (11/23/04):

Bozeman is an interesting case study because it is small and because the Smart Growthers have strong control of the city…Our Column in Today’s Gazette: The Hidden Risks of ‘Smart Growth’

…the real problem is that city and county officials are trying to stop suburban growth around the city by imposing Portland-style growth controls. Officials insist that new developments are far more densely packed than the market demands…

On a practical level, these Smart Growth policies are counterproductive. Restricting growth in the city, or creating unattractive high-density projects in a place awash in open space, only pushes people farther out into the countryside. In Belgrade, eight miles away, one finds market-driven suburban-style subdivisions. That city does not have many restrictions, and those who cannot afford Bozeman or who want a bigger place simply move away, thus promoting the sprawl that Smart Growthers are trying to stop…

The Portland, Ore., metro region is considered a smart growth pioneer, going back to the early 1970s. Portland adopted urban growth boundary restrictions to preserve open space outside the boundary. Transportation initiatives have emphasized public transit over road-building…

Many homebuyers, especially those with children, began to avoid Portland in their quest for affordable, conventional homes with yards. This ironically fostered sprawl (PDF) and traffic as people migrated to cities outside the region’s authority, such as Vancouver, Wash.

Berkeley, California: Cautions on Infill

In 1990, 60 percent of New Yorkers said they would live somewhere else if they could, and in 2000, 70 percent of urbanites in Britain felt the same way. Many suburbanites commute hours every day just to have “a home, a bit of private space, and fresh air.”

Downtown house on “dead end street” in “rural setting” flies off market

…there are excellent reasons for many homebuyers to desire cul-de-sacs and leafy neighborhoods. Planners who ignore these strong (and logical) market preferences risk making sprawl worse, as some buyers may come to avoid downtown Northampton and seek these amenities in the outskirts or even out of town.

Greening Smart Growth: The Sustainable Sites Initiative

The presence of natural elements has several implications for personal and community security. Shared green spaces, particularly those with trees, provide settings for people to interact and strengthen social ties. Residential areas with green surroundings are associated with greater social cohesion in neighborhoods, and neighbors with stronger social ties are more likely to monitor local activity, intervene if problem behaviors occur,[48] and defend their neighborhoods against crime.[49] Residents of buildings with greater tree and grass cover report fewer incidences of vandalism, graffiti, and litter than counterparts in more barren buildings.[50] Likewise, a study comparing police reports of crime and extent of tree and grass cover found that the greener a building’s surroundings, the fewer total crimes were reported.[51]

UMass Press: “Natural Land: Preserving and Funding Open Space”

Preserving areas of nature, open space, and trees and other vegetation can have psychological as well as physical health benefits for local residents. There is a growing body of research which points to the power of nature to restore people from the stress of modern life, including mental fatigue (Kaplan, Kaplan, and Ryan 1998; Frumkin 2001).

Terrain.org: The Breath of Trees Is Good for You

…I am breathing deeply of a forest gift that I had forgotten: the air! Americans have largely ignored this dimension of the forest’s allure, but the Japanese recognize it and have a name for it: shinrin-yoku, wood-air bathing. Japanese researchers have discovered that when diabetic patients walk through the forest, their blood sugar drops to healthier levels. The Japanese have hosted whole symposiums on the benefits of wood-air bathing and walking…

Scientists Assist Efforts to Build Urban Tree Canopy

Downstreet.net: “Despite Tree City USA Honor Northampton Planting Lags”

Smart Growth with Balance: The American Planning Association [emphasis added]

Green infrastructure is an interconnected network of greenways and natural lands that includes wild life habitat, waterways, native species and preservation or protection of ecological processes. All development — including redevelopment, infill development, and new construction in urbanizing areas — should plan for biodiversity and incorporate green infrastructure. Green infrastructure helps to maintain natural ecosystems, including clean air and water; reduces wildlife habitat fragmentation, pollution, and other threats to biodiversity. It also improves the quality of life for people.

Topographical Map Shows How Kohl Condo Proposal Will Eat Into a Rare Stand of Mature Trees in Downtown

Photo Essay: Millyard Brook Swells with Water in Winter

Photo Essay: Our Woods in Winter

Photo Essay: The Forest Behind View Avenue